Entrevista a Chomsky: “la participación directa en la creatividad”

Publicado el 07 Enero 2010. Tags: Alternativas, información, medios de comunicación, misinformación, Noam Chomsky, Poder, politica, propaganda, Resistencia, verdad

ESCUCHA LA ENTREVISTA COMPLETA 28 minutos

English version of this article and interview transcript below

Traducción de la entrevista en español abajo

“La participación directa en la creatividad”

por Eric French Monge

Crear algo nuevo en medio de tanto ruido. Eso es lo que nos proponemos en Amauta: imaginar una revista que de el espacio para debatir seriamente sobre el sufrimiento, las opresiones, las dudas y esperanzas de cualquiera que quiera participar. Nos bombarden con información constante, pero no nos sentimos bien informados, y supuestamente el conocimiento trae poder, pero nunca nos hemos sentido más impotentes. Estas frustraciones que sentimos son reales. ¿Pero de dónde vienen y por qué no podemos enfrentarnos a ellas adecuadamente?

Hay demasiado ruido. Nos lanzan bombas de información por todas partes que nos atacan el cuerpo hasta paralizarnos. Antes creíamos en todo lo que se nos decía, y ahora no creemos en nada. Al final, es el mismo efecto. No queremos participar ni controlar nuestros destinos, entonces le damos el poder sobre nuestras vidas a políticos y a corporaciones por medio del voto o de la compra de sus productos. Ahora ellos toman las decisiones y crean las estructuras que forman nuestra vida diaria. Si deciden mal, les podemos echar la culpa y sentirnos contentos y superiores de que lo hubieramos hecho mejor. Son culpables, porque la responsabilidad y la capacidad de destrucción de sus actos crece con la cantidad de poder que les demos, pero nosotros lo somos también. Preferimos refugiarnos en espacios de información cada vez más cerrados y pequeños donde encontremos gente que piensa como nosotros, donde nos sintamos cómodos y no tengamos que enfrentar crítica alguna. Nos convertimos en burbujas andantes donde nada más podemos escucharnos a nosotros mismos. Preservamos nuestro individualismo y variedad de opiniones, pero al final llegamos a ser lo mismo: gente que no puede escuchar al resto y darse cuenta que comparten realidades similares, gente que sigue dividida porque sólo pueden oír el ruido de su propia voz, gente que sigue dominada porque no puede formar la acción colectiva necesaria para recuperar el poder que hemos regalado. Los que tienen control sobre nuestras vidas quieren que nos mantengamos aislados para que no haya posibilidad de un cambio radical. Y por eso Amauta quiere abrir el espacio, conversar con los demás, formar una comunidad en donde todos podamos participar como iguales, llegar a encontrar información que nos lleve a cuestionar nuestras ideas y creencias hasta tener las ganas de actuar juntos para poder, en algún momento, reestablecer el control de nuestra vida. Aquí en este instante, hablándonos, creamos el primer acto de nuestra resistencia.

Pero para la creación de tal espacio, se ocupa conocer y entender cómo y por qué los medios de comunicación presentes contribuyen a nuestro dominio. De ellos obtenemos nuestra información, la cual influye nuestras ideas de la realidad y basamos nuestra relación al mundo y la forma determinada de como vamos a actuar en él. Si las noticias que recibimos de los medios pronuncian, por ejemplo, que la única forma de salvar la economía, y de esta manera a nosotros mismos, es comprando más, entonces vamos a seguir esta recomendación. Es algo tan fundamental para nuestro tipo de vida que nuestra posición social, y nuestra felicidad, solo se puede garantizar por medio de la capacidad que tenemos de poder comprar. Y como creemos completamente en esta doctrina del consumismo, hemos explotado y abusado nuestros recursos a tal punto de destrucción que se nos hace difícil poder detenerla. Hemos menospreciado las necesidades del medio ambiente, al igual que las del resto de la humanidad, para en vez buscar la ilusión de la seguridad personal que trae nuestro bienestar material. Los medios de comunicación han difundido esta idea a todos los rincones del planeta porque es la “verdad” que fue permitida atravesar los diferentes filtros de poder para que resonara a través de la sociedad, de esta forma convirtiédose en la única opción realista para nuestras vidas.

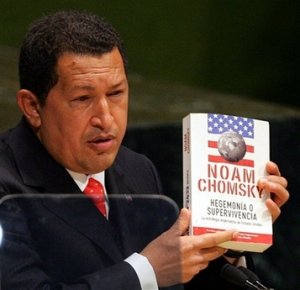

Ésta es, en la mayoría de casos, nuestra realidad. Pero no tiene que serla. Sencillamente es lo que nos han dicho, y por eso vemos el mundo de tal forma. Para desenmascarar las influencias que dominan la estructura de nuestros medios de comunicación actuales (y de esta forma las verdades que son permitidas en nuestra sociedad) y poder enfrentarnos a ellas para cambiarlas, decidimos (y tuvimos la gran oportunidad de) hablar con uno de los intelectuales públicos y lingüistas que ha estudiado el tema a profundidad: Noam Chomsky. El coautor con Edward S. Herman de Los Guardianes de la Libertad (en inglés, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media) y autor de obras como Ilusiones Necesarias y Propaganda y la Opinión Pública (a través de las entrevistas de David Barsamian), Chomsky demuestra como los medios de comunicación han sido herramientas de propaganda que filtran los pensamientos “inadecuados” y así propagan las ideas dominantes de aquellos, que por circumstancias económicas o (y) políticas, tienen los recursos para ocupar puestos sociales que les den acceso a ampliar sus voces, mientras el resto tiene derecho (o deber) de escucharles. Él no cree que estas ideas dominantes sean iguales entre sí (puede haber diferencia entre intereses estatales y corporativos, por ejemplo), o que los periodistas no estén ejerciendo su profesión con honestidad y cierta independencia, o que hayan pequeños grupos de poder que planean conspiraciones y están decididos a engañar y manipular en gran escala por su propio beneficio. Piensa que los parámetros de control que limitan la discusión se imponen a través de un sistema basado en la acumulación de recursos: el que tiene más dinero y más poder va a tener mejor accesso a los medios de comunicación para expresar sus preferencias e ideologías. Lo logra porque, sencillamente, puede comprar ese espacio y restringir la competencia solo a aquellos que piensan dedicar esta información a fines comerciales o valores “aceptables” como mantener el orden social, la conformidad y el consumismo incuestionable como el rol en nuestra vida. Así lo explica Chomsky en nuestra reciente conversación:

“Muchas personas en los medios de comunicación son gente muy seria, y honesta, y te dirán, y creo que tienen razón, que no los fuerzan a escribir nada [...] Lo que no te dirán, y tal vez no estén concientes de ello, es que los dejan escribir con libertad porque se ajustan a las normas, sus creencias se ajustan … a la doctrina del sistema, y entonces sí, los dejan escribir con libertad y sin presión. Las personas que no aceptan la doctrina del sistema intentarán sobrevivir dentro de los medios de comunicación, pero es muy poco probable que lo hagan…

Toda la cultura intelectual tiene un sistema que filtra, empieza cuando uno es niño en la escuela. Se espera que aceptes ciertas creencias, estilos, patrones de conducta, y así. Si no los aceptas, puede que te llamen un problema, que tienes un comportamiento problemático, y te eliminan. Esto ocurre en las universidades. Hay un sistema implícito que filtra y crea una fuerte tendencia a imponer conformidad. Sin embargo, es una tendencia, entonces van a haber excepciones, y a veces las excepciones son bien asombrosas. Por ejemplo, esta universidad [Massachusetts Institute of Technology], en la década de los 60s, en el periodo de activismo de los 60s, la universidad fue financiada casi un cien por ciento por el Pentágono. También fue uno de los principales centros académicos de resistencia en contra de la guerra [Vietnam]…

Las tendencias son bien fuertes, y las recompensas para la conformidad son bastantes altas, mientras los castigos por no conformarse pueden tener serias consecuencias. No es como si te fueramos a mandar a una camara de tortura [...], pero podría afectar tu ascenso en la sociedad, te podría afectar hasta tu empleo, te podria afectar la forma en la que eres tratado, sabes, como el desprecio, el rechazo, la difamación y denuncia.”

Pero Chomsky insiste que esto ha ocurrido en toda sociedad a traves de la historia. La persecusión de aquellos que han cuestionado las creencias opresivas que las autoridades dictan se observa desde la Grecia antigua y la era bíblica porque “los sectores de poder no van a querer que prospere la disidencia por la misma razón que las empresas no van a poner anuncios en periódicos como La Jornada.”

A mediados de septiembre, Chomsky fue uno de los invitados de honor para el aniversario de 25 años de La Jornada, el cual considera “el único periódico independiente en todo el hemisferio.” Sin embargo, dice que le sorprende el éxito de este diario mexicano no solo porque sobrevive sin muchos anuncios, pero también porque toca temas de suma importancia que están fuera de los límites de lo considerado “aceptable” y continúa siendo una de las principales y más populares fuentes de información en el país. Normalmente, como en su propio país de los Estados Unidos, los medios de comunicación como el New York Times y CBS News cumplen una función fundamental apoyando los sectores de poder porque su “liberalismo” los convierte en “guardianes de las compuertas” que marcan que se puede publicar y que no. “Creo que son moderadamente críticos dentro de los márgenes. No están totalmente sometidos al poder, pero son bien estrictos en que tan lejos se puede ir,” declara Chomsky. Cita el ejemplo de la guerra contra Vietnam, donde los medios de comunicación no cuestionaban las intenciones del gobierno, ya que creen que siempre esta intentando de “hacer el bien”, pero sí llegan a criticar sus planes, sus estrategias y, quizas, los abusos cometidos cuando fracasan en su misión o se esta muriendo tanta gente que no se puede ocultar más al descaro. A Obama también se le llama “liberal”, dice Chomsky, porque criticó el gobierno anterior por sus errores estratégicos y no tanto porque haya pensado que la guerra de Irak o Afganistán en sí sean malas. En estos momentos, después de la escalada de tropas en Afganistán, Chomsky demostró tener razón: Obama es “liberal” no porque cuestiona las intenciones bélicas del estado, sino porque piensa poder hacerlo mejor.

Se les llaman “liberales” no porque lo sean, pero porque es lo más extremo a la izquierda que se pueda llegar donde los sectores de poder aún sigan cómodos que no vaya a haber algo que afecte la jerarquía establecida. Según un estudio del Pew Research Center, solo “29 por ciento de los estadounidenses dicen que las organizaciones de noticia por lo general reportan los hechos correctamente” mientras que “más del doble [de los encuestados] dicen que la prensa es más liberal que los que dicen que es conservadora.” Como mucho del pueblo estadunidense ve a los medios de comunicación como entidades liberales, hay un empuje hacia la derecha de parte de muchos como respuesta. Los locutores de radio y televisión de la derecha en Estados Unidos tienen “un mensaje uniforme” que atrae una “audiencia enorme” porque se dirigen a las “quejas auténticas” de sus oyentes, afirma Chomsky.

“Ponte en la posición de una persona, dizque el estadounidense común: ‘Soy un buen trabajador y cristiano devoto. Cuido a mi familia, voy a misa, sabes, hago todo “bien”. Y estoy siendo timado! En los últimos treinta años, mis ingresos siguen estancados, mis horas de trabajo suben y mis prestaciones sociales bajan. Mi esposa tiene que trabajar dos empleos para poder traer comida al hogar. Los niños, Dios, no hay quien cuide a los niños, las escuelas son terribles y así. ¿Qué hice mal? Hice todo lo que se debe hacer, pero algo injusto me esta ocurriendo.’ Y entonces los locutores derechistas tienen una respuesta para ellos…”

Estos locutores se aprovechan y explotan el descontento legítimo de los afectados por las falsas promesas de los gobernantes, las mentiras de los medios de comunicación y las estafas de las corporaciones. Desconfían porque les han pintado una vida que no existe en su horizonte, porque su realidad es otra, más severa pero desinfectada para que los que sí tienen poder para cambiar sus circumstancias puedan tragarse la historia de que el sistema actual funciona perfectamente. Para los sectores de poder, el capitalismo ha funcionado y ha sido maravilloso, y como esa es su realidad, eso es lo que creen y van a predicar. Y como tienen el control de los aparatos para hacerse escuchar de forma extensa, ese es el único ruido que en verdad sobresale de los demás. Para muchos, como él mismo, reconoce Chomsky, “nos está yendo bien. Por ejemplo, hay muchas quejas sobre el sistema médico, pero yo recibo asistencia médica estupenda. Nuestra asistencia médica se distribuye en base a la riqueza, y para [cierto tipo de gente] todo está bien. Pero no para aquellas personas que escuchan estos programas, y esa es una gran parte de la población.” Entonces estos locutores logran, por el simple hecho de al menos admitir de que existen problemas, convertirse en una voz potente en defensa de aquellos que fueron relegados al margen de la sociedad, y así, irónicamente, acumulan su propio poder y mucho dinero comercializando el apoyo y confianza de los oyentes. Mientrás se hacen ricos, ofrecen falsas soluciones populistas que enfoca la rabia digna del pueblo en contra de “inmigrantes” o “socialistas” o “feministas” que supuestamente tienen el control total del gobierno, y así crean pleitos entre personas con problemas similares y los distraen del hecho de que estos supuestos líderes también se enriquecen con el sistema actual y promueven, más bien, un mundo donde sus ideas, la de los hombres blancos y ricos, sea ley suprema. O sea, lo que están haciendo es reforzar el sistema existente y excluir a mucho más gente que antes de los pocos beneficios que provee. Pero estas contradicciones se pierden en los gritos que pegan, ahogándonos en el ruido del miedo y de la ira.

¿Cómo podemos entonces enfrentarnos y resistir ideas fáciles que tienden a engañarnos y obstaculizar un cambio aútentico? ¿Se podrá? ¿Se ha logrado?

“[Estos patrones] se han roto hasta cierto punto. Es por eso que ya no vivimos en tiranía, sabes, el rey ya no decide lo que es permitido, y hay mucho mas libertad de lo que hubo en el pasado. Entonces sí, estos patrones se pueden alterar. Pero mientras exista la concentración del poder de una u otra forma, sea de armas, capital o de otra cosa, mientras haya concentración de poder, estas consecuencias [las tendencias para conformarse dentro del marco social] son de esperarse.”

Chomsky menciona encontrarse con cierta frustración dentro de los círculos de intelectuales izquierdistas en su reciente viaje a México porque sienten “que hay cierta inquietud y activismo popular, pero muy fragmentado. Que estos grupos tienen agendas muy limitadas y específicas a ciertas luchas y no se relacionan ni colaboran entre sí. Bueno, eso es algo que hay superar si se quiere construir un movimiento popular amplio. Y los medios de comunicación pueden ayudar…” pero “[s]e ocupa organización. La organización y la educación, cuando interactuan una con la otra se fortalecen entre sí, se apoyan mutuamente.”

Amauta entonces quiere intentar crear el espacio donde diferentes personas y grupos puedan debatir, sea cual sea la ideología, en torno a los problemas sinceros de nuestras comunidades y no como una herramienta de propaganda o de interés propio. Donde, quizá, podamos ser los dueños de nuestras propias voces, y nuestra palabra valga mas que la palabra del político en la televisión, y nuestra conversación nos informe más de lo que pueda informarnos los medios de comunicación actuales. Pero más que todo, queremos expandir la conversación a todo rincón posible para colaborar y participar juntos en un movimiento o varios movimientos que perturben y cambian el estado actual de nuestro mundo. Como lo escribió Chomsky en su libro Democracia y Educación, “un movimiento izquierdista no tiene oportunidad de éxito, y no la merece, sino obtiene un entendimiento de la sociedad contemporánea y una visión para un orden social futuro que sea convincente para la gran mayoría de la población. Sus metas y estructuras organizativas deben formarse a través de la participación activa del pueblo dentro las luchas populares y la reconstrucción social. Una cultura radical auténtica solo se puede crear a través de la transformación espiritual de un enorme número de personas, en el cual el rasgo esencial de cualquier revolución social es la de extender las posibilidades de creatividad humana y de la libertad.”

Para retomar nuestra voz y convertirnos en artistas, periodistas, creadores de nuestra verdad e impulsores del cambio, Chomsky nos dió un ejemplo práctico de lo que considera “una participación directa en la creatividad.” Comenta que hace alrededor quince años en Brasil, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, en aquel entonces un sindicalista que aún no era presidente, lo llevó a un barrio en las afueras de Río de Janeiro en donde había un espacio abierto, una plaza. “Es un país semi-tropical, todo el mundo esta afuera, es de noche. Un pequeño grupo de periodistas de Río, profesionales, salieron esa noche con un camión que parquearon en el medio de esa plaza. El camión tenía una pantalla encima de él, y un equipo de transmisión televisiva. Y lo que estaban transmitiendo eran obras, escritas por la gente de la comunidad, actuadas y dirigidas por las personas en la comunidad. Entonces las personas del barrio están presentando estas obras, y una de las actrices, una muchacha, tal vez de diecisiete, estaba caminando en medio de la multitud con un micrófono, preguntándole a la gente que comentara- hay muchas personas ahí, y están interesadas, mirando, hay gente sentada en los bares, gente andando por la plaza – entonces comentaron sobre lo que vieron. Y como había un pantalla, se transmitían en vivo lo que decía la gente sobre la obra, y después otros respondían a lo que se dijo, y así. Y estas obras eran substanciales… Trataban [temas] serios. Algunas de las obras eran comedias, sabes, pero trataban temas como la crisis de la deuda pública, o del sida. … Fue una participación directa en la creatividad. Y creo que fue algo bastante ingenioso.”

Ahora nos toca a nosotros. Queremos ser esa plaza, ese espacio público donde la comunidad se una para crear algo primordial. Buscar activamente que más y más gente participe directamente para incitar una transformación comunal, y quiza algún día, una revolución auténtica. Si quieres unirte, bienvenido.

Transcripción completa de la entrevista

Entrevista realizada por Eric French Monge

Traducción: Alejandro Sánchez

Amauta: Quería empezar la conversación con tu reciente viaje a América Latina. Escuché que estuviste en América Latina, y en México este fin de semana y lunes. ¿Cómo estuvo? Sólo una noción general.

Chomsky: Estuve en Ciudad de México. Es una ciudad muy placentera en muchos aspectos. Es vibrante, enérgica y con una sociedad muy emocionante. De la misma manera, es depresiva en otros aspectos y a veces casi desesperante, tú sabes. Es decir, es una combinación de vitalidad y, no diría desesperación, sino desesperanza, tú sabes. Eso no tiene que ser, pero así es. O sea, casi no hay economía.

Amauta: Y fuiste exclusivamente por el aniversario de “La Jornada”?

Chomsky: La Jornada es, en mi opinión, el único periódico independiente en todo el hemisferio.

Amauta: Sí.

Chomsky: Y sorprendentemente exitoso. Es el segundo periódico más grande en México, y está muy cerca del primero. Es completamente boicoteado por los anunciantes, así que cuando lo lees, tengo una copia acá, pero si tú solo pasas las hojas, no hay anuncios. No porque ellos se nieguen, sino porque los negocios no pagan por ello. Aunque ellos tienen anuncios, son anuncios de alguna reunión o del gobierno, es porque la constitución así lo demanda. Pero a pesar de ser boicoteados, sobreviven y florecen.

Amauta: ¿Por qué cree usted que hay éxito?, ¿Por qué cree que es exitoso?

Chomsky: Yo no podría descifrar eso, no estoy seguro, ellos saben como hacerlo (se ríe). Pero es increíblemente sorprendente, y, por supuesto, muy inusual ya que todos los medios de comunicación dependen de publicidad para sobrevivir. Y además es independiente. Me refiero a que sólo estuve ahí 4 días, y aún así debí haber recogido seis noticias que son importantes y que no aparecen en la prensa internacional.

Amauta: Voy a hacer un resumen general de lo que ha dicho. Usted dice que al ser los medios un negocio, el cuál tiene que obtener ganancias, responde a la demanda del mercado y sus inversionistas en vez de la integridad de las noticias. Se limita su contenido a lo que es aceptable dentro de los límites de la ideología capitalista, promoviendo la agenda y valores capitalistas en toda la sociedad. Mantiene el orden social, la conformidad y el consumismo indiscutible como nuestro papel en la vida. Y como las corporaciones que controlan los medios reúnen y tiene mayor acceso al mercado, limitan aún más la información y debaten de lo que está adentro de los intereses de unos pocos.

¿Ves a los medios de comunicación participando en algún tipo de control de la mente, o esto sería demasiado fuerte para una declaración?

Chomsky: bueno, primero que todo, creo que es una relación muy estrecha, ya que se ajustan estupendamente a los intereses del Estado. El sistema estatal y el sistema de la empresa son cercanos, pero no son idénticos. También tenemos que reconocer que hay una serie de intereses. Es decir, no hay un único interés de las empresas ni un único interés del estado. Además de esto, se encuentra la integridad profesional. Mucha gente involucrada en los medios es honesta y seria. Ellos te dirían, y creo que tienen razón, que nadie los obliga a escribir nada.

Amauta: que son objetivos………?

Chomsky: ….. No, ellos creen que lo son. Lo que no te dicen, y de lo cual son talvez ignorantes, es que se les permite escribir libremente porque sus creencias se ajustan generalmente a la doctrina del sistema. Por consiguiente, sí escriben libremente sin ser obligados. La gente que no acepta la doctrina del sistema puede tratar de sobrevivir en los medios, pero es poco probable. Así que hay un rango. Sin embargo, hay un tipo de conformidad fundamental que es un requisito para entrar en los medios de comunicación. Ahora, ya sabes, no es una sociedad totalitaria, de modo que hay excepciones, puedes encontrarlas. Por otra parte, los medios de comunicación no son muy diferentes de las universidades en este sentido. Es decir, hay un efecto real por parte de la publicidad, de la propiedad de las empresas y del Estado. Estos son en gran medida los acontecimientos que responden a una cultura intelectual.

Amauta: ¿Así que piensas que son los valores que mantiene la gente lo que influye en eso?

Chomsky: Toda la cultura intelectual posee un sistema de filtrado que empieza desde la escuela. Se espera que aceptes ciertas creencias, estilos, patrones de comportamiento, y así por el estilo. Si no los aceptas, te dicen que padeces de problemas de conducta o algo y eres descartado. Algo así pasa también a lo largo del camino en las universidades y en las escuelas de postgrado. Hay un sistema de filtrado implícito que tiene, que crea una fuerte tendencia a imponer el conformismo. Ahora bien, es una tendencia, por lo que tiene excepciones, y a veces las excepciones son muy notables. Tomemos como ejemplo la Universidad MIT (Massachussets Intitute of Technology) en los 60’s. En el periodo de activismo de los 60’s, estaba casi al cien por ciento financiada por el Pentágono. Y era a la vez, de manera muy probable, el mayor centro académico de resistencia “anti-guerra”.

Amauta: Sí, vi una oficina de la Lockheed Martin en el piso de abajo (de la MIT).

Chomsky: sí, ahora hay una oficina de la Lockheed Martin. No había en ese momento, se ha vuelto más empresarial desde entonces. Así es la industria militar, pero en aquel momento era directamente financiada por el Pentágono. De hecho, yo estaba en un laboratorio que era cien por ciento financiado por el Pentágono, y fue uno de los centros del movimiento organizado de resistencia contra la guerra.

Amauta: Así que usted dice que hay una ventana de oportunidad para la resistencia?

Chomsky: Hay un conjunto de posibilidades. Tiene límites, ya sabes. Las tendencias son un poco fuertes, las recompensas para la conformidad son bastante altas y los castigos para la inconformidad pueden ser significativos. Aunque no es que les enviamos a una cámara de tortura.

Amauta: (Risa) Más como forma de vida y cómo las cosas te limitan…?

Chomsky: Puede ser, puede afectar el progreso, puede afectar incluso el empleo. Puede afectar la forma en que eres tratada, ya sabes: menosprecio, despido, difamación, denuncias. Hay una serie de aspectos que podría afectar, y es una verdad de cada sociedad.

Amauta: entonces piensas que está arraigado en nuestra cultura? Algo así?

Chomsky: No, es de cada sociedad. No sé de ninguna sociedad que se haya diferenciado en ese sentido.

Volvamos a la época clásica, por ejemplo a la Grecia antigua. ¿Quién bebía la cicuta (1)? ¿Era alguien que estaba conforme, obedeciendo a los dioses? ¿O era alguien que estaba perturbando a la juventud y cuestionando la fe y la creencia? En otras palabras, era Sócrates. O volvamos a la Biblia, al viejo testamento. Quiero decir que hay gente que podríamos llamar intelectuales. Ahí fueron llamados profetas, pero fueron básicamente intelectuales: eran personas que estaban haciendo análisis crítico y geopolítico, hablaban de las decisiones del rey que llevarían a la destrucción, condenaban la inmoralidad, y pedían justicia para las viudas y los huérfanos. Lo que podríamos llamar intelectuales disidentes. ¿Los trataban bien? No, fueron llevados al desierto, fueron encarcelados y fueron juzgados. Fueron intelectuales que se conformaron. Siglos más tarde, digamos que en los Evangelios, fueron llamados los falsos profetas, pero no en el momento. Ellos fueron los únicos bienvenidos y bien tratados en aquel entonces: los abanderados de la corte. Y yo no sé, no conozco de ninguna sociedad que se diferencie en eso. Hay una variación, por supuesto, pero ese modelo básico persiste; y es completamente comprensible. Quiero decir, los sectores de poder no van a favorecer el florecimiento de la disidencia; es la misma razón por la cuál las empresas no se anuncian en La Jornada. (1 La cicuta, planta tóxica, cuyo nombre científico es Conium maculatum, del que se extrae un veneno que recibe el mismo nombre y que era usada por los antiguos griegos para quitarse la vida.)

Amauta: ¿Crees que podemos romper este modelo?

Chomsky: Se ha quebrado en cierta medida. Es decir, no vivimos en tiranías, ya sabes, el rey no decide lo que es legítimo, y hay mucha más libertad de la que había antes. Así que, sí, estos modelos pueden ser modificados. Mientras haya concentración de poder en una forma u otra, ya sea de armas o de capital o cualquier otra cosa, estas consecuencias se esperan casi automáticamente.

Como digo, hay excepciones. Es interesante ver las excepciones. Por ejemplo la suya (La Jornada), o Occidente por completo. Sólo sé de un país, por lo menos a mi conocimiento, que tiene una cultura disidente. En la cuál las figuras principales, es decir, los más famosos escritores, periodistas, académicos y otros, no son sólo críticos de la política estatal. Sino también hacen surgir una desobediencia civil, toman el riesgo de encarcelamiento y a menudo son encarcelados. Ese país es Turquía.

En Europa occidental, Turquía es considerada como incivilizada, por lo que no puede entrar en la Unión Europea hasta que sea civilizada. Creo que es al revés, si se pudiera alcanzar el nivel de civilización de los intelectuales turcos, sería todo un logro.

Amauta: Usted ha escrito que si el público tiene sus “propias fuentes de información independientes, la línea oficial del gobierno y la clase empresarial serían cuestionados”. Según un estudio de Pew Research Center, sólo “el 29% de los estadounidenses dicen que las organizaciones de noticias en general obtienen los hechos reales”. Sin embargo, “el doble decía que la prensa era más liberal que conservadora” que ha dado lugar a más divisiones entre las personas y la desconfianza de unos a otros…

Chomsky: Sí, yo diría lo mismo. Creo que la prensa, a lo largo y ancho, es lo que llamamos “liberal”. Pero, por supuesto lo que llamamos “liberal” significa bueno para la derecha. Liberal significa los “guardianes de las puertas”. Así, el New York Times es “liberal” por, lo que se llama, los estándares del discurso político. El New York Times es liberal, CBS es liberal, no discrepo. Creo que son moderadamente críticos en los márgenes. No están totalmente subordinados al poder, pero son muy estrictos en que tan lejos puedes ir. Y de hecho, su liberalismo cumple una función muy importante de apoyo en el poder. Es decir: “Soy el guardián de las puertas, puedes llegar hasta aquí pero no mas allá”.

Tomemos un hecho más relevante: la invasión a Vietnam. Bueno, ningún periódico liberal jamás habló de la invasión de Vietnam; se habló de la defensa de Vietnam. Y poco después decían: “Bueno, no está marchando bien”. OK, eso los hace liberales. Es como, si dijéramos, si volviéramos a la Alemania Nazi, y que el personal general de Hitler fuera liberal después del Stalingrado porque estaban criticando sus tácticas: “Fue un error luchar en dos frentes, tuvimos que haber derrotado a Inglaterra en primer lugar,” o algo así. OK, a eso llamamos liberalismo, decir: “no está marchando bien”, o: “talvez no está costando demasiado”. Quizá, algunos puedan decir siquiera: “talvez estemos matando demasiada gente”. Pero eso sigue siendo “liberal”. Toma como ejemplo a Obama. Es llamado liberal y elogiado por sus “principios de oposición a la guerra de Irak”. Cuál fue su principio de oposición? Él dice que fue un “error estratégico”, igual que los generales nazis después de Stalingrado. OK, bueno…

Amauta: no la guerra misma, sino…

Chomsky: No es que había algo necesariamente malo con ello, sino que fue un “error estratégico”: “no debimos haberlo hecho, debimos haber hecho otra cosa” como “no debimos haber peleado en 2 frentes” como si estuviera en el personal alemán. O como, Pravda en los 80’s, es decir, pudiste haber leído cosas en Pravda diciendo que era una estupidez invadir Afganistán: “es una tontería, tenemos que salir, nos está costando demasiado”. Quiero decir que allí el equivalente estadounidense sería “liberalismo extremo”, y ha sido muy bien estudiado. Digamos que la guerra de Vietnam se prolongó durante mucho tiempo, tenemos gran cantidad de material. Lo que se llamó “la crítica extrema de la guerra”. Digamos justo al final de la guerra, yendo demasiado lejos, lo que se llama la “extrema izquierda” de los medios de comunicación, quizá Anthony Lewis y el New York Times: abiertos, liberales, la “extrema”. Lewis resumió la guerra en 1975 diciendo que los Estados Unidos entró a Vietnam del Sur con, creo que la frase fue: “esfuerzos fallidos para hacer el bien”. “Para hacer el bien” es redundante. Nuestro gobierno dio una definición de lo que es “hacer el bien” y trata de darle evidencia, no lo hace porque es una redundancia, es como decir: “dos más dos son cuatro”. Así que entramos, de una manera torpe, sí, no resultó. Así que entramos con “esfuerzos fallidos por hacer el bien”, pero en 1969, fue evidente que era un desastre demasiado costoso para nosotros. No pudimos llevar democracia y libertad a Vietnam a un costo aceptable para nosotros mismos. La idea de que eso era lo que tratábamos de hacer es, de nuevo, una redundancia. Es verdad por definición, ya que lo estábamos haciendo; y el Estado es noble por definición. Eso se llama “liberalismo extremo”.

Amauta: estás diciendo que periódicos como el New York Times son…

Chomsky: Son liberales.

Amauta: …el lado liberal para el público en general.

Chomsky: Son liberales por nuestras normas, por las normas convencionales del liberalismo.

Amauta: Esto significa que si el doble de las personas dicen esto, son también liberales…

Chomsky: Tienen razón, tienen razón. Pero no es lo que quieren dar a entender. Veamos, eso no es lo que quieren decir quienes responden a la pregunta. Es por eso que estaría de acuerdo con ellos, pero con una interpretación diferente. Lo que estoy diciendo es que, lo que se llama “liberal” en la cultura intelectual significa: muy conformista con el poder, pero levemente crítico. Como, por ejemplo, Pravda en los años 1980, o el personal alemán después de Stalingrado. Altamente conformista con el poder, pero crítico, quizás muy crítico. Porque es cometer un error, o nos está costando mucho, o no es el mejor accionar, o algo. Sí, eso es liberal, es lo que llamamos liberal. Sin embargo, cuando la gente responde esa pregunta, se refieren a algo más. A lo que probablemente se refieran, ya sabes, las encuestas no lo muestran realmente, pero adivinando, mi suposición sería que ellos se refieren a los estilos de vida. Así como aceptan el aborto, no son religiosos, viven un estilo de vida más o menos libre, no como las familias tradicionales, creen en los derechos de los gays, y cosas así por el estilo. Lo que las encuestas no te dicen, aunque algunas sí, es que si usted realiza un estudio de los directores ejecutivos, los altos ejecutivos en las empresas, son liberales. Sus opiniones en estas cuestiones son casi las mismas que las de la prensa.

Amauta: ¿Cree usted que…

Chomsky: A propósito, si escuchas los programas de entrevistas, que son rabiosos de derecha, y muy interesante, un dato importante sobre los Estados Unidos, es que logran una audiencia enorme. Y son muy iguales. Así la derecha, no creo que incluso usted pueda encontrar un equivalente, pero ellos llegan a un público masivo, y su punto de vista es que las corporaciones son liberales. El llamado a la población es: “El país es gobernado por los liberales, ellos poseen las empresas, manejan el gobierno, son dueños de los medios de comunicación, y no se preocupan por nosotros, la gente común”. Y hay un equivalente a esto: los finales de la República de Weimar, es muy semejante a los finales de la República de Weimar. Y a su vez, este llamado masivo tiene sus similitudes con la propaganda Nazi. Y… importante…muchas diferencias, pero hay un sentido muy importante en el que es similar: ellos están llegando a una población de personas con verdaderas quejas. Las quejas no son inventadas. En los Estados Unidos, en Weimar…

Amauta: Esa era mi pregunta, ¿si estas gentes desconfían, podrían llegar a tener una sana desconfianza de los medios; pero pueden, tú crees, ser manipulados por otros intereses extremos?

Chomsky: Bueno, yo realmente sugiero escuchar los programas de radio. Me refiero a que, si sólo escuchas lo que los presentadores dicen, suenan como si estuvieran locos.

Amauta: Y también tienen tanta cobertura en los medios de comunicación.

Chomsky: Pero, pon de lado tu incredulidad y sólo escúchalo. Ponte en la situación de una persona, un estadounidense promedio, “soy una persona trabajadora, un cristiano temeroso de Dios, me ocupo de mi familia, hago todo ‘bien’. Y estoy siendo follado. Durante los últimos treinta años, mi ingreso se ha estancado, mis horas de trabajo están aumentando, mis beneficios están disminuyendo. Mi esposa tiene que trabajar en 2 empleos para, ya sabes, poner comida en la mesa. Los niños, Dios, no hay cuidado para los niños, las escuelas están podridas, etc. ¿Qué hice mal? Hice todo lo que se supone debes haces, pero algo malo me está pasando“.Ahora, los presentadores de programas tienen una respuesta, nadie tiene una respuesta, quiero decir, hay una respuesta.

Amauta: Cierto, ellos dirigen sus quejas.

Chomsky: Bueno, la respuesta es, ya sabes, la refundación neoliberal de la economía, entre otras cosas. Pero nadie les da esa respuesta. No los medios exactamente porque ellos no lo ven de esa manera, lo hacen muy bien. Como, por ejemplo, Anthony Lewis, en el extremo izquierdo, describe los últimos treinta años como la edad de oro de, la edad de oro del capitalismo estadounidense. Bueno, lo fue para él y sus amigos. Y para mí. Ya sabes, las personas con nuestro nivel de ingresos les va bien. Al igual, hay quejas sobre los servicios de salud, sí. Yo consigo asistencia médica excelente.

Amauta: Tú trabajas en la universidad.

[Pequeña interrupción haciéndome saber que la entrevista se estaba acabando]

Chomsky: Nuestro sistema de salud está condicionado por la riqueza. Y la gente con la que Anthony Lewis va a cenar a un restaurante, y sus amigos, sí, para ellos está bien. Pero no para la gente que está escuchando el programa, que es la mayor parte de la población. De hecho, para la mayoría de la población, los salarios e ingresos se han estancado y las condiciones han empeorado. Entonces, ellos se preguntan: ¿Qué hice mal? Y la repuesta que el presentador del programa les está dando es convincente, en su lógica interna. Está diciendo, “los que está mal es que los liberales son dueños de todo, manejan todo, no se preocupan por usted; por lo tanto, desconfía de ellos”. ¿Qué dijo Hitler? Dijo lo mismo. Él dijo “son los judíos, son los bolcheviques”, eso es…

Amauta: Estaba culpando a otros.

Chomsky: …Eso es una respuesta. Está bien, eso es una respuesta. Y tiene una lógica interna, quizá loca, pero tiene una lógica interna.

Amauta: Una última pregunta. Partiendo de allí, y para contrarrestar estas, supongo que, la derecha…

Chomsky: Populismo, eso es lo que es.

Amauta: …Sí, populismo. Dijiste que para construir un movimiento, los medios de comunicación deben de participar en la construcción de los mismos. Esto es lo mío [parafraseando]. Pero, para construir un movimiento, se necesita un llamado de base amplia, una “cultura radical genuina sólo puede crearse mediante la transformación espiritual de las grandes masas de personas, la característica esencial de toda revolución social consiste en ampliar las posibilidades para la creatividad humana y la libertad”. ¿Cómo pueden los medios de comunicación alternativa, como Amauta, impulsarse a sí mismos en la construcción de este “llamado de base amplia” e ir más allá de “convencer al convencido”? Porque yo siento que muchos de los medios alternativos son leídos por gente con “X” afinidad política. Por ejemplo, yo leo ciertas cosas, yo leo La Jornada, pero, ¿sólo personas como yo lee La Jornada? ¿Otras gentes leen La Jornada? A la gente no le gusta ser desafiada.

Chomsky: La Jornada es ampliamente leído. Por ejemplo, tú puedes ir por las calles, y ver a alguien de pie, o sentado en un bar leyéndolo. Pero, los medios por sí solos no son suficientes. Tienes que tener una organización. Toma a México como ejemplo. Digo, no pretendo saber mucho sobre México, pero hablé con un buen número de intelectuales mexicanos de izquierda, y todos dijeron lo mismo. Que hay una gran preocupación popular y un poco de activismo, pero todo está muy fragmentado. Que los grupos tienen agendas estrechas muy específicas y ellos no interactúan ni cooperan entre ellos. Ok, eso es algo que hay que superar para construir un movimiento popular de masas. Es ahí donde los medios pueden ayudar, pero se benefician de ello. Pero tienes razón, si eso no ocurre, si no obtenemos el tipo de integración de las preocupaciones y mecanismos de los activistas, cada movimiento seguirá “convenciendo al convencido”.

Amauta: Entonces, ¿crees que tenemos que involucrar a la gente, pero instándolas con una participación activa…?

Chomsky: Se requiere una organización. Organización y educación, cuando interactúan entre sí, se refuerzan, se apoyan mutuamente.

Amauta: ¿Cómo te imaginas la existencia de una red de personas de todas las partes de la sociedad, pero sobre todo la mayoría que necesita para tener su voz de vuelta, convirtiéndose ellos mismos en expertos como periodistas-ciudadanos, o en artistas, mientras se hacen mutuamente responsables en el proceso crear la noticia?

Chomsky: De un montón de maneras. Debo irme, pero te daré un ejemplo práctica entre muchos otros. Hace aproximadamente 15 años, estuve en Brasil, viajé mucho por allí con Lula en aquel tiempo. Él todavía no era el presidente. Me llevó una vez a un gran suburbio en las fueras de Rió de Janeiro, con un par de millones de personas, un barrio pobre. Y tenía un gran espacio abierto, una especie de plaza al aire libre. Es un país semi-tropical, todo mundo estaba afuera, era de noche. Un pequeño grupo de periodistas y profesionales, de Río, salían por la noche en un camión, y lo estacionaban en el medio de la plaza. El camión tenía una pantalla encima y un equipo de transmisión. Y lo que ellos transmitían eran parodias escritas, actuadas y dirigidas por gente de la comunidad. Así, la población local presentaba sus parodias. Una de las actrices, una chica de unos 17 años talvez, caminaba entre la multitud con un micrófono invitando a la gente a comentar –un montón de gente estaba allí, estaban interesados, estaban viendo, tú sabes, gente sentada en barras de metal, o dando vueltas por el lugar-, y así comentaban sobre lo que vieron, y lo que decían era transmitido, ya sabes, había una pantalla detrás que mostraba lo que la persona decía, y después otra gente comentaba. Y las parodias eran significativas. Ya sabes, yo no sé portugués, pero podía entender más o menos.

Amauta: Entonces, ¿ves esta actividad como una participación activa?

Chomsky: Por supuesto, había parodias serias, algunas otras eran comedia, Pero algunas eran, ya sabes, sobre la crisis de la deuda, o sobre el SIDA…

Amauta: Pero permite un espacio para la creatividad, para la gente…

Chomsky: Es la participación directa en la creatividad. Y era una cosa muy imaginativa a realizar, creo. No sé si aún se lleva a cabo, pero es uno de los muchos modelos posibles.

“Direct participation in creativity”

The creation of something innovative and powerful in the midst of so much white noise. That is what we are proposing for Amauta. Imagine a magazine that gives space to the serious debate of the suffering, oppressions, doubts and hopes of whomever wants to participate. In today’s media driven world, we are bombarded with constant information, and yet we still feel uninformed. Knowledge is power, but we continue to feel powerless in our own lives. These frustrations and impotence that we feel are real. But where are they coming from and why can’t we confront them properly?

There is too much noise. They throw bombs of information at us from all sides that attack our bodies until we are paralyzed and unable to gain a deeper understanding from what is being said. Before, we believed everything they told us, and now, we don’t believe in anything. In the end, it has the same effect. We neither want to participate nor control our destinies, so we give power over our lives to politicians and corporations by means of voting (in the booth or the checkout line) Now, these people we have elected make the decisions and create the framework that structures our daily lives. If they make a bad decision, we can blame them and feel content and superior that we could have done it better. These powerful men and women are to blame, as the responsibility and capacity to destroy grows with the amount of power we give them, but we are at fault as well. We prefer to seek refuge in information spaces that are progressively smaller and increasingly closed off from any opinions which we do not share. Here in these comfortable spaces, we do not have to face any criticism because we find people who think like us. We preserve our individuality and variety in thinking, but at the end we become the same: people who cannot listen to each other and are incapable of realizing that they share similar realities; people who continue to drift away from each other because they can only listen to the noise of their own voice; people that keep being held back because we cannot take the necessary collective action to regain the power we have given away. Those who have control over our lives want us to stay isolated from each other so there is no possibility of radical change. That is why Amauta wants to open up a space where we can talk to each other and form a community where everyone can participate as equals. As we discover information that leads us to question our ideas and beliefs, we will develop a drive to act together so we can, at some moment, re-establish control over our lives. Here, at this moment, in the simple act of talking with each other and opening ourselves up to understanding, we create our first act of resistance.

But to create such a space, we need to understand how and why current communication media contribute to contain and manipulate us. We obtain most of our information from these outlets. This influences our perceptions of reality, and thus our relationship to this world and the particular way we decide to act in it. For example, if the news we receive through mainstream media sources establishes that the only way we can save our economy, and thus ourselves, is to buy more, then we will tend to do just that. This is such a central part of our way of life that our social status, and our happiness, is determined by this ability to buy. Yet since we wholeheartedly believe in this doctrine of consumerism, we have exploited and abused our resources to a point of destruction that it is hard to go back from. We have undermined the needs of the environment, as well as our fellow human beings, for the sake of our personal quest for self-satisfaction. Media has perpetuated this idea far and wide because it is the “truth” that was allowed to go through the different filters of power to reverberate throughout society–thus becoming the only option that is realistic for our lives.

This is, in the majority of cases, our reality. But it doesn’t have to be. It is simply what they have told us it is, and that is why we see the world in that way. To unmask the influences that dominate the infrastructure of our current media (and thus the truths that are allowed in our society) so we can confront and change them, we had the amazing opportunity to talk to a well-respected public intellectual and linguist who has studied the subject in depth: Noam Chomsky. Coauthor with Edward S. Herman of Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media, and author of works such as Necessary Illusions and Propaganda and the Public Mind (through interviews by David Barsamian), Chomsky demonstrates how mass media have been propaganda tools that filter “inadequate” thoughts, and therefore spread the prevailing ideas of those who, by economic and/or political circumstances, have the resources to hold social positions that give them access to amplify their voices, while the rest has the right (or duty) to listen to them. He does not believe that these dominant ideas are one and the same (there can be differences between state and corporate interests, for example), or that journalists are not trying to do their job honestly and with some independence, or that small powerful groups conspire to deceive and manipulate in large scales for their own benefit. He considers that these parameters of control that limit debate become established through a system based on the accumulation of goods and influence: those who have more money and more power are going to have better access to media to express their priorities and ideologies. They manage to do this simply because they have the resources to buy this space and restrict competition to those who consider dedicating information to commercial ends or who share “acceptable” values such as social order, conformance and unquestionable consumerism as our roles in life. This is how Chomsky explains it in our recent conversation:

“A lot of the people involved in the media are very serious, honest people, and they will tell you, and I think they are right, that they are not being forced to write anything… What they don’t tell you, and are maybe unaware of, is that they are allowed to write freely because their beliefs conform to the … standard doctrinal system, and then, yes, they are allowed to write freely and are not coerced. People who don’t accept that doctrinal system, they may try to survive in the media, but they are unlikely to…

The whole intellectual culture has a filtering system, start[ing] as a child in school. You’re expected to accept certain beliefs, styles, behavioral patterns and so on. If you don’t accept them, you are called maybe a behavioral problem, or something, and you’re weeded out. Something like that goes on all the way through universities and graduate schools. There is an implicit system of filtering…which creates a strong tendency to impose conformism. Now, it’s a tendency, so you do have exceptions, and sometimes the exceptions are quite striking. Take, say, this university [Massachusetts Institute of Technology], in the 1960s, in the period of 60s activism, the university was about a hundred percent funded by the Pentagon. It was also, probably the main academic center of antiwar resistance [during the war in Vietnam]….

The tendencies are quite strong, and the rewards for conformity are quite high, and the punishments for nonconformity can be significant. It’s not like we send you to a torture chamber,…[but] it can affect advancement, it can affect even employment, it can affect the way you’re treated, you know, disparegeament, dismissal, slander, denunciations.”

But he insists that this filtering system has existed in all societies throughout history. The persecution of those who have questioned oppressive beliefs dictated by the authorities can be observed since ancient Greece and biblical times. This persecution continues because “sectors of power are not going to favor the flourishing of dissidence; the same reason why businesses won’t advertise in La Jornada.”

In the middle of September, Chomsky was one of the guests of honor for La Jornada’s twenty-fifth anniversary, which he considers to be “the one independent newspaper in the whole hemisphere.” He says that this Mexican daily’s success surprises him not only because it survives without much advertising, but also because it deals with important subjects that are outside the limits of what is considered “acceptable” and yet continues to be one of the most popular mainstream news sources in the whole country. Normally, Chomsky thinks that the larger and more established media sources like the New York Times and CBS News “serve an extremely important function in supporting power” because their “liberalism” turns them into “the guardians of the gate” as they draw a line on what can be published and what cannot. “I think they’re moderately critical at the fringes. They’re not totally subordinate to power, but they are very strict in how far you can go,” he said. He gives the example of the war against Vietnam: people in the mainstream media would not really question the government’s intentions, since they mostly believed that the government was always trying “to do good.” They might have criticized its plans, strategies and, just sometimes, denounced the abuses committed after its forces failed a mission or after the amount of people who had died couldn’t be hidden anymore from the public, but not the underlying intent. They also called Obama a “liberal”, Chomsky says, because he criticized the previous government for its “strategic blunder” and not so much because he thought that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan themselves are bad. At this time, after the announcement of a troop surge in Afghanistan, Chomsky showed he was right: Obama is a “liberal” not because he questions the war-driven intentions of this nation, but because he believes he can do it better.

Most media are labeled as “liberal” not because they really are, but because they are as far left as they can go in the political spectrum without making the people in power uncomfortable. According to a recent Pew Research Center survey, only “29 percent of Americans say that news organizations generally get the facts straight”, while twice as many of those surveyed said the press was liberal compared to those who said it was conservative. If the general public perception of mainstream media is of a deceptive liberal entity, then it follows that there would be a push to the right by many people. Right-wing talk show hosts have a “uniform” message that “reach a huge audience” because they address people’s “real grievances”, Chomsky asserts.

“Put yourself in the position of a person, sort of an ordinary American, ‘I’m a hard-working, god-fearing Christian. I take care of my family, I go to church, I…do everything ‘right’. And I’m getting shafted. For the last thirty years, my income has stagnated, my working hours are going up, my benefits are going down. My wife has to work two [jobs] to…put food on the table. The children, God, there’s no care for the children, the schools are rotten, and so on. What did I do wrong? I did everything you’re supposed to do, but something’s going wrong to me.’ Now the talk show hosts have an answer…”

An atmosphere of mistrust towards so called ‘liberal’ media allows for extreme right outlets to exploit the genuine grief of those affected by politicians’ fake promises, medias’ lies and corporations’ frauds. These people mistrust media because they have been painted a life that does not exist in their horizon since their reality is something else: much harsher but sanitized so those who actually do have power to change these circumstances can swallow the story that this current system works perfectly. For those in sectors of power, capitalism has worked and has been wonderful, and since that is their reality, that is what they are going to believe and preach. And because they have control of the devices to make themselves be heard far and wide, this is the only noise that really stands out from the rest. For many, including himself, Chomsky acknowledges, “people at our income level are doing fine. Like, there’s complaints about health care, yeah. I get terrific health care… Our health care is rationed by wealth, and [for certain people] it is fine. But not for the people who are listening to the talk shows, and that’s a large part of the population.” So these outlets manage, from the simple act of admitting that problems exist, to turn into a powerful voice that defends those who have been pushed into the sidelines of society. In this way, ironically, they then accumulate their own power and money by marketing their listeners’ support and trust. While they become rich, they offer false populist solutions that direct the people’s rightful rage against “immigrants” or “socialists” or “feminists” that supposedly have the government under control. By creating fights between groups with similar problems, right wing media manages to distract people from the fact that they themselves (these so-called advocates) also profit from the current system. They are able to continue to promote a world where their ideas, those of rich white men, is supreme law. In other words, what this actually accomplishes is to reinforce the existing system and exclude more people than before from the little benefits the system provides. But these contradictions easily get lost in their shouts, drowning everything in the noise of fear and rage.

How can we face and resist easy ideas that end up misleading us and obstruct genuine change? Can it be done? Has it been done?

“[These patterns have] been broken to an extent. So we don’t live in tyrannies– the king doesn’t decide what’s legitimate, and there’s much more freedom than there was in the past. So yes, these patterns can be modified. But as long as you have concentration of power in one form or another, whether it’s arms, or capital or something else, when you have concentration of power, these are consequences that you almost automatically expect.”

Chomsky notes he found some frustration within leftist intellectuals in his recent visit to Mexico because they feel “there’s a lot of popular… concern and activism, but it is very fragmented. That the groups have very specific, narrow agendas and they don’t interact and cooperate with one another. Ok, that’s something you have to overcome to build a mass popular movement. And… media can help, but they also benefit from it, so… unless that happens, unless you get kind of an integration of activists’ concerns and movements… each one will be ‘preaching to the choir’… It takes organization. Organization and education, when they interact with each other, they strengthen each other, they are mutually supportive.”

Amauta would like to facilitate the creation of this coordinated popular movement. We will create a space where different people and groups could discuss, no matter what ideology, our communities’ troubles with sincerity. At the same time, we would remain conscious of the importance of not allowing Amauta to become an instrument for propaganda or self-interest. Here, perhaps, we could become masters of our own voices, and our word would be worth more than that of the politician on television, and our conversation would reveal more than any information we obtain from current mass media. Most importantly, we would like to expand our conversation until it reaches every possible corner so that we can all collaborate to form a movement or many movements that disrupt and transform the current state of affairs in our world. As Chomsky wrote in his book, Chomsky on Democracy and Education, “a movement of the left has no chance of success, and deserves none, unless it can develop an understanding of contemporary society and a vision of a future social order that is persuasive to a large majority of the population. Its goals and organizational forms must take shape through their active participation in popular struggle and social reconstruction. A genuine radical culture can be created only through the spiritual transformation of great masses of people, the essential feature of any social revolution that is to extend the possibilities for human creativity and freedom.”

To reclaim our voice and become artists, journalists, creators of our own truths and instigators of change, Chomsky gave us a practical example of what he considers “direct participation in creativity.” He describes how more or less fifteen years ago in Brazil, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, in those times a labor unionist not yet president, took him to a poor neighborhood outside Rio de Janeiro where there was an open space: a town square. “It’s a semi-tropical country, everybody’s outside, it’s in the evening. A small group of journalists from Rio, professionals, come out in the evening with a truck, park it in the middle of the plaza. It has a screen above it. And broadcasting equipment. And what they’re braodcasting [are] skits, written by people in the community, acted and directed by people in the community. So local people are presenting the skits. One of the actresses, girl, maybe seventeen, was walking around the crowd with a microphone, asking people to comment – a lot of people were there, and they were interested, they were watching, you know, people sitting in the bars, people milling around in the space – so they commented on what they saw, and what they said was broadcasted, you know, there was a television screen behind, so they displayed what the person said, and then other people commented on that. And the skits were significant [...], there were about serious… some of them were comedy, you know. But some of it was [...] about the debt crisis, or about AIDS [...] It’s direct participation in creativity. And it was a pretty imaginative thing to do, I think.”

Now it is our turn. We want to be that town square, that public space where communities can gather to create something of paramount importance. We want to actively seek out more and more people to directly participate to incite a communal transformation, and perhaps one day, an authentic revolution. If you want to join us, welcome.

Interview transcript

Amauta: So I wanted to start the conversation with your recent trip to Latin America. I just heard you were in Latin America and you were in Mexico this Monday and this weekend. How was it? Just a general statement.

Chomsky: I was in Mexico City. It’s a very pleasant city in many ways. It’s vibrant, lively, pretty exciting society, but also depressing in other ways, and sometimes almost hopeless, you know. So it’s a combination of vibrancy and, I wouldn’t say despair, but hopelessness, you know. Doesn’t have to be, but it is. I mean, there is almost no economy.

Amauta: And you went there specifically for the anniversary of La Jornada?

Chomsky: La Jornada, which is, in my opinion, the one independent newspaper in the whole hemisphere.

Amauta: Yeah.

Chomsky: And amazingly succesful. So it is now the second largest newspaper in Mexico, and very close to the first. It is completely boicotted by advertisers, so when you read it, I have a copy of it here, but if you just thumb through it, there is no ads. Not because they refuse them, but because business won’t advertise. Though they have notices, you know, so announcements of a meeting, they have government notices. But that is only because the constitution requires it. But they are essentially boicotted. But nevertheless they survive and flourish.

Amauta: Why do you think there is success, why do you think its succesful?

Chomsky: I couldn’t figure that out, and I am not sure they know. (Laugh). But it is amazingly succesful, and of course, it is extremely unusual because all media depend on advertisement to survive. And it is also independent, I mean, I was only there four days, but I must have picked up half a dozen articles that don’t appear in the international press, that are important.

Amauta: I’m going to make a general summary of some of your work. You say, Because media is a business, which has to create profits, it answers to the market demands and its investors more than to the integrity of the news. It constrains its contents to what is acceptable within the limits of capitalist ideology, promoting the capitalist agenda and values throughout society. It maintains social order, conformance and unquestionable consumerism as our roles in life. And as the corporations that control media conglomerate and have larger access to the market, they further limit information and debate to what is within the interests of even fewer powerful people.

Do you see media engaging in some sort of soft mind control, or would this be too strong of a statement?

Chomsky: Well, first of all, I think that is a bit too narrow because they also conform very stupendously to state interests, and that state system and the corporate system are close, but they are not identical. And also we have to recognize that there is a range of interests, like there isn’t a single corporate interest and a single state interest, so there’s a range. In addition to that, there is the fact of professional integrity. A lot of the people involved in the media are very serious, honest people, and they will tell you, and I think they are right, that they are not being forced to write anything…

Amauta: That they are objective.

Chomsky: …not that they believe in. What they don’t tell you, and are maybe unaware of, is that they are allowed to write freely because they conform, their beliefs conform to the generally, you know, to the standard doctrinal system, and then, yes, they are allowed to write freely and are not coerced. People who don’t accept that doctrinal system, they may try to survive in the media, but they are unlikely to. So there’s a range. But there is kind of a fundamental conformity, which is a virtual requirement to enter into the media. Now, you know, it’s not a totalitarian society, so there’s exceptions. You can find exceptions. Furthermore, the media are not very different from universities in this respect. So it’s really, there’s an effect of advertising, corporate ownership, the state, there’s an effect. But this are really to a large extent current events now of an intelectual culture. You don’t…

Amauta: So you think it’s more like the values people hold influence this.

Chomsky: The whole intelectual culture has a filtering system, starts as a child in school. You’re expected to accept certain beliefs, styles, behavioral patterns and so on. If you don’t accept them, you are called maybe a behavioral problem, or something, and you’re weeded out. Something like that goes on all the way through universities and graduate schools. There is an implicit system of filtering, which has the, it creates a strong tendency to impose conformism. Now, it’s a tendency, so you do have exceptions, and sometimes the exceptions are quite striking. Take, say, this university [MIT], in the 1960s, in the period of 60s activism, the university was about a hundred percent funded by the Pentagon. It was also, probably the main academic center of antiwar resistance.

Amauta: Yeah, I saw a Lockheed Martin office downstairs.

Chomsky: Yeah, now there is a Lockheed Martin office. There wasn’t at that time, it has become more corporate since. That’s the military industry, but at that time it was straight Pentagon funding. In fact, I was in a lab that was a hundred percent funded by the Pentagon, and it was one of the centers of the organized antiwar resistance movement.

Amauta: So you do say there is a window of opportunity for resistance?

Chomsky: There’s a range of possibilities. It has limits, you know, and the tendencies are quite strong, and the rewards for conformity are quite high, and the punishments for nonconformity can be significant. It’s not like we send you to a torture chamber.

Amauta: (Laugh)More like lifestyle and how things limit you to certain…

Chomsky: It can be, it can affect advancement, it can affect even employment, it can affect the way you’re treated, you know, disparegeament, dismissal, slander, denunciations. There’s a range of, it’s true of every society.

Amauta: So you think it’s like engrained in our culture, kind of.

Chomsky: No, it’s every society. I don’t know of any society throughout history that’s been unlike it.

Go back to classical times, say classical Greece. Who drank the hemlock? Was it someone who was conforming, obeying the gods? Or was it someone who was disrupting the youth and questioning the faith and belief? Socrates, in other words. It was Socrates. Or go back to the Bible, the Old Testament. I mean there were people who we would call intelectuals, there, they were called prophets, but they were basically intelectuals: they were people who were doing critical, geopolitical analysis, talking about the decisions of the king were going to lead to destruction; condemning inmorality, calling for justice for widows and orphans. What we would call dissident intelectuals. Were they nicely treated? No, they were driven into the desert, they were imprisoned, they were denounced. They were intelectuals who conformed. Centuries later, let’s say in the Gospels, they were called false prophets, but not at the time. They were the ones who were welcomed and well-treated at the time: the flaggers of the court. And I don’t know, I know of no society since that is different from that. There is variation of course, but that basic pattern persists, and it is completely understandable. I mean, sectors of power are not going to favor the flourishing of dissidence; the same reason why businesses won’t advertise in La Jornada.

Amauta: Do you think we could break that pattern?

Chomsky: It’s been broken to an extent. So we don’t live in tyrannies, you know, the king doesn’t decide what’s legitimate, and there’s much more freedom than there was in the past. So yes, these patterns can be modified. But as long as you have concentration of power in one form or another, whether it’s arms, or capital or something else, when you have concentration of power, these are consequences that you almost automatically expect.

As I say, there are exceptions. It’s interesting to see the exceptions. So take your, or the West altogether. I know of only one country, at least to my knowledge, which has a dissident culture where leading figures, I mean, the most famous writers, journalists, academics and so on, are not only critical of state policy, but are constantly carrying out civil disobedience and risking imprisonment and often being imprisoned, standing up for people’s rights. That’s Turkey.

In Western Europe, Turkey is regarded as uncivilized, so they can’t come in into the European Union until they’re civilized. I think it’s the other way around. If you could achieve the level of civilization of, say, Turkish intelectuals, it would be quite an achievement.

Amauta: You have written that if the public have their “own independent sources of information, the official line of the government and the corporate class would be doubted”. According to a Pew Research Center study, only “29% of Americans say that news organizations generally get the facts straight”, Yet “twice as many saying the press was liberal than conservative”, which has lead to more divisions among people and distrust of each other…

Chomsky: Yeah, I would say the same thing. That I think the press, by and large, is what we call “liberal”. But of course what we call “liberal” means well to the right. “Liberal” means the “guardians of the gates”. So the New York Times is “liberal” by, what’s called, the standards of political discourse, New York Times is liberal, CBS is liberal. I don’t disagree. I think they’re moderately critical at the fringes. They’re not totally subordinate to power, but they are very strict in how far you can go. And in fact, their liberalism serves an extremely important function in supporting power. It’s saying: “I’m guardian of the gates, you can go this far, but not further.”

So take a major issue, like say, the invasion of Vietnam. Well, no liberal newspaper ever talked about the invasion of Vietnam; they talked about the defense of Vietnam. And then they were saying, “well, it’s not going well.” Ok, that make them liberal. It’s like, it’s if we were to say, that going back to, say, Nazi Germany, that Hitler’s general staff was liberal after Stalingrad because they were criticizing his tactics: “It was a mistake to fight a two front war, we should’ve knocked off Englad first,” or something. Ok, that’s what we call liberalism, saying, “well it’s not going well,” you know, so, “maybe it’s costing us too much” or you know some may say even “maybe we are killing too many people.” But that’s called “liberal.” So take like, say, Obama, he’s called “liberal” and he’s praised for his “principled objection to the Iraq war”. What was his “principled objection”? He says it was a “strategic blunder,” like Nazi generals after Stalingrad. Ok, well…

Amauta: Not the war itself, but…

Chomsky: Not that there was necesarily something wrong with it, but that it was a “strategic blunder”: “we shouldn’t have done it, we should have done some other thing” like “we shouldn’t have fought a two front war” if you are on the German general staff. Or like, let’s take Pravda in the 1980s. I mean you could have read things in Pravda saying that it was a stupid error to invade Afghanistan: “it was a dumb thing to do, we have to get out, it’s costing us too much.” I mean that U.S. analog of that would be “extreme liberalism,” and it has been pretty well studied. Let’s say the Vietnam war went on for a long time, we have a ton of material. What was called “the extreme critique of the war,” let’s say right at the war’s end, you go too way, what’s called the “far left” of the media, maybe Anthony Lewis and the New York Times, outspoken, liberal, the “extreme”. He summed up the war in 1975 by saying the U.S. entered South Vietnam with, I think his phrase was, “blundering efforts to do good.” “To do good” is tautological. Our government did it so therefore by definition of what’s “to do good” and try to give evidence to that, he doesn’t because it’s a tautology, it’s like saying two plus two equals four. So we enter, and blundering, yeah, it didn’t work out, well. So we enter with “blundering efforts to do good,” but by 1969, it was becoming clear that it was a disaster too costly to ourselves. We could not bring democracy and freedom to Vietnam at a cost acceptable to ourselves. The idea that that was what we were trying to do, is again, a tautology, it’s true by definition because we were doing, and the state is noble by definition. That’s called “extreme liberalism”.

Amauta: So you are saying that papers like the New York Times are…

Chomsky: They are liberal.

Amauta: …the liberal side for the general public.

Chomsky: They’re liberal by our standards, by the conventional standards of liberalism.

Amauta: That means that if twice as many people are saying these are too liberal…

Chomsky: They are right. They are right. But that’s not what they mean. See, that’s not what the people mean who are answering the question. That’s why I would agree with them, but with a different interpretation. I’m saying what’s called “liberal” in the intelectual culture means highly conformist to power, but mildly critical. Like, say, Pravda in the 1980s, or the German general staff after Stalingrad. Higly conformist to power, but critical, maybe even sharply critical. Because it’s making a mistake, or it’s costing us too much, or it’s the wrong thing to do, or something. Yeah, that’s liberal, that’s what we call liberal. But when the people are answering that question, they mean something else. What they mean probably, you know, the polls don’t really inquire, so we don’t know, but guessing, my guess would be what they mean is, they are referring to their lifestly choices. So like they accept abortion, they are not religious, you know, they live more or less free lifestyle, not the traditional families, they believe in gay rights, and so on. What the polls don’t tell you is, though other polls do, is that if you do a study of CEOs, top executives in corporations, they’re liberal. Their additudes on these matters are about the same as the press.

Amauta: Do you think…

Chomsky: And incidentally, if you listen to the talk shows, which are rabid right-wing, and very interesting, an important fact about the United States, they reach a huge audience. And they’re very uniform. So right wing, I don’t think you can even find an analog in your, but they reach a mass audience, and their view is that the corporations are liberal. Their appeal to the population is, “the country is run by liberals, they own the corporations, they run the government, they own the media, and they don’t care about us ordinary people.” And there’s an analog to this: late Weimar republic, it’s very reminiscent of the late Weimar republic. And this mass appeal has it’s similitarities to Nazi propaganda. And… an imporant… and a lot of differences, but there’s a very important sense in which it’s similar: they are reaching out to a population of people with real grievances. The grievances are not invented. In the United States, in Weimar Germany…

Amauta: That was my question, if these people distrust, they might have a healthy distrust of the media, but they can, you think, be manipulated by other extreme interests?

Chomsky: Well, I really suggest listening to talk radio. I mean, if you just listen to what the talk hosts are saying, they sound like they are lunatics.

Amauta: And they have so much coverage in the media too.

Chomsky: But put aside your disbelief and just listen to it. Put yourself in the position of a person, sort of an ordinary American, “I’m a hard-working, god-fearing Christian. I take care of my family, I go to church, I, you know, do everything ‘right’. And I’m getting shafted. For the last thirty years, my income has stagnated, my working hours are going up, my benefits are going down. My wife has to work two [jobs] to, you know, put food on the table. The children, God, there’s no care for the children, the schools are rotten, and so on. What did I do wrong? I did everything you’re supposed to do, but something’s going wrong to me. Now, the talk show hosts have an answer, nobody has an answer, I mean, there is an answer.

Amauta: Right, they address their grievances.

Chomsky: Well, the answer is, you know, the neoliberal remaking of the economy, among other things. But nobody is giving them that answer. Not the media certainly because they don’t see it that way, they’re doing fine. Like, say, Anthony Lewis again in the way left end describes the last thirty years as the golden age of, the golden age of American capitalism. Well, it was for him and his friends. And for me. You know, people at our income level are doing fine. Like, there’s complaints about health care, yeah. I get terrific health care.

Amauta: You work in the university.

[minor interruption, letting me know time of interview was running out]

Chomsky: Our health care is rationed by wealth. And the people Anthony Lewis meets for dinner in a restaurant, and his friends and so on, yeah, for them is fine. But not for the people who are listening to the talk shows, and that’s a large part of the population. In fact, for the majority of the population, wages and incomes have stagnated and conditions have gotten worse. So they are asking, “what did I do wrong?” And the answer that the talk show host is giving them is convincing, in it’s internal logic. It’s saying, “what’s wrong is the rich liberals own everything, run everything, they don’t care about you; therefore, distrust them” and so on. What did Hitler say? He said the same thing. He said “it’s the Jews, it’s the Bolcheviks, that’s a….

Amauta: He was scapegoating.

Chomsky: …that’s an answer. Ok, it is an answer, internal to… and it has an internal logic, maybe insane, but it has an internal logic.

Amauta: So, one last question. Going from there, and to counteract these, I guess, right-wing…

Chomsky: Populism. That’s what it is.